The Spectre of censorship has visited Hollywood’s secret service agent in India, where 007’s kissing scenes have been cut by half. But there’s more than meets the eye. Dennis Hanlon and Shorna Pal explain.

On 19 November 2015, the day before it was due to be released in Indian theatres, the Times of India announced that the Central Board of Film Censorship (CBFC) had ordered the kissing scenes in the latest James Bond film, Spectre, to be reduced by half.

The UK press reacted with predictably swift and condescending criticism. Articles with titles such as ‘India CUTS James Bond’s kissing scenes in SPECTRE as they’re deemed too graphic’ (The Mirror) and ‘Bond and gagged: Spectre’s kissing scenes censored by Indian film certification board (The Guardian) revived caricatures of Indian cinemas as prudish, with women singing in wet saris replacing nudity and, of course, the mythical absolute ban on kissing.

And yet, the truth is that Indian film censorship has never been as lenient as it is today. Ironically, this very point was made by Pahlaj Nihalani, Chairman of the CBFC and the official who ordered the cuts, when he noted during a televised Times Now Debate interview the kissing scenes had been completely removed from the previous entry in the Bond franchise, Skyfall (2012).

One might be inclined to think that Indian audiences would be appreciative of such progress, but such was not the case. The cuts sparked outrage among India’s fast-growing middle class. They also incited a revolt among some members of the CBFC’s board because Mr Nihalani, who freely admitted to not having seen the film, arguing that that was the job of the board, had overruled its recommendations by fiat.

This is much more than a tempest stirred up in a martini shaker, but to understand why requires knowledge of the political nature of Indian film censorship as well as recent changes in production and consumption of cinema in India.

The CBFC is housed within the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and its members are political appointees. Since it was established in 1952, it has been plagued by claims of political coercion and corruption. Mr Nihalani was installed in January 2015 after the previous chair, Leela Samson, along with 12 board members, resigned, arguing an appellate board had overruled the CBFC under political pressure in a case involving a film starring a controversial guru. Her predecessor had been arrested for corruption a mere five months earlier.

Once Samson and her colleagues had resigned, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government of Narendra Modi appointed Mr Nihalani, a known BJP sympathiser, as chairman. On the face of it, Mr Nihalani seemed an unlikely choice for Modi to make as chair; as a producer in Bollywood in the 1990s, he was known for the coarse content of his films and especially their sexually suggestive song lyrics. Since those days, though, he seems to have had a moral and political conversion; in November of this year he uploaded videos to his YouTube channel with titles such as My Country is Great and A Modi in Every Home.

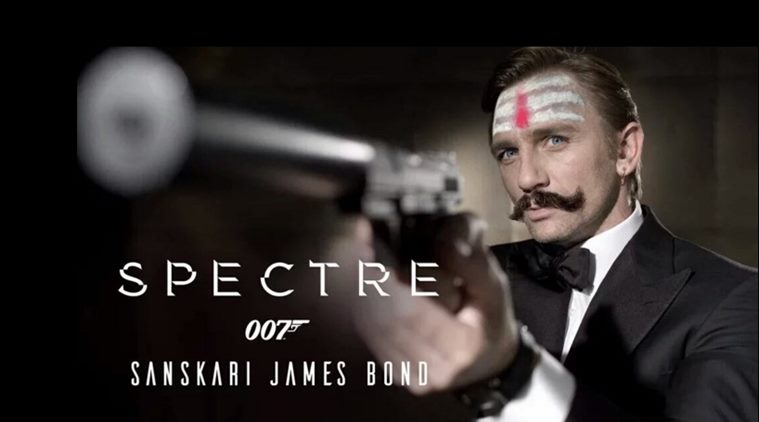

The #sanskarijamesbond meme on Twitter.

In retrospect, Mr Nihalani seems the perfect figure to navigate the CBFC through the double bind in which Modi’s government finds itself. It simultaneously appeals to two groups whose interests are not always easily reconciled; the poor who can be swayed by displays of Hindu nationalism, and the business elites fond of his neoliberal economic policies. As a BJP stalwart, Mr Nihalani appeals to the former, and his experience within the film industry, including a lengthy stint as president of the Association of Motion Picture and TV Programme Producers, makes him trusted by the latter. Bollywood, after all, is an export jewel in the crown of India’s glory for Modi’s government, which explains in part why film censorship, while still subject to arbitrary political manipulation, continues to loosen. Producers know that for films to succeed abroad, they must approximate international norms.

In the past, when non-Indian films could scarcely muster 5 per cent of ticket sales, cuts to an imported film would hardly have been noticed, much less elicit outrage. Today, however, Hollywood studios such as Sony and Walt Disney are moving in, creating studio branches in India. And their films are gaining traction in a marketplace now dominated by westernised middle class viewers who view them in high-priced multiplexes rather than the large single-screen theatres in which Mr Nihalani’s 1990s fare played to large audiences of mostly proletariat, or even lumpenproletariat, men.

These expanding middle class audiences, so key to Modi’s economic strategies, have increasingly little patience with the CBFC’s moral policing of their films. Thus, when Mr Nihalani responded to charges of hypocrisy by saying he had “always been sanskaari [virtuous]”, the middle class twitterati responded with ♯SanskariJamesBond, memes in which Bond girls appeared in traditional dress and Daniel Craig’s face was adorned with vibhuti, sacred ash associated with Hinduism.

While this controversy is bound to play out again with future releases, it remains to be seen whether the CBFC has been shaken to its core or stirred to more extreme action. Given the increasing censorship across other media in India, the smart bet might be on the latter.