Bangalore is one of the fastest growing cities in India, but its growth is marred by social inequalities.

As the fifth largest metropolitan city of India, Bangalore has its own story of growth. Popular for its pleasant climate and numerous gardens and lakes, it is known today as India’s Silicon Valley for its vibrant IT sector which co-exists with other small and medium industries. This photo essay attempts to visually represent the manifestations of development in urban life in and around Bangalore. The city is connected to neighbouring regions through industrial corridors and national highways. Within Bangalore, urban life is heterogeneous; residents include high-income gated communities on one end of the spectrum and resource-constrained slum dwellers at the other end.

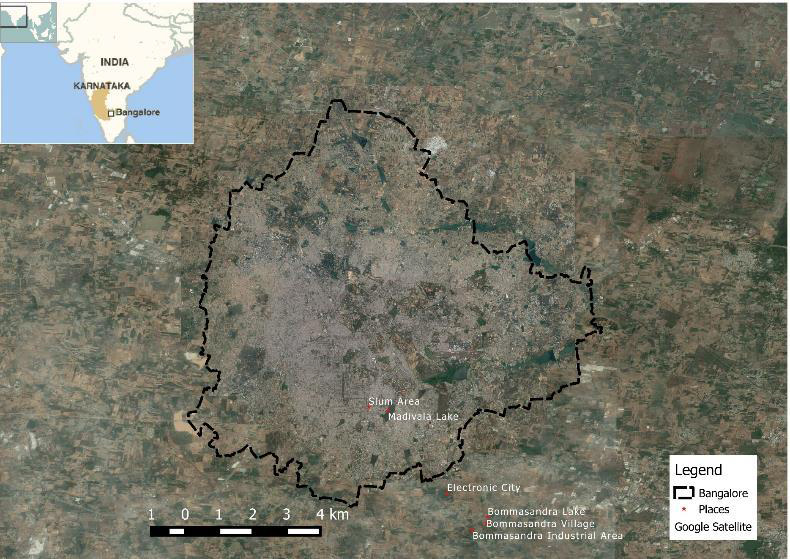

This photo essay captures urbanity in two clusters in Bangalore. First, along the National Highway 7, towards south Bangalore, there are two small townships, Electronic City and Bommasandra Industrial Town, representing contrasting modes of urbanisation and governance. Second, residential layouts along Bannerghatta Road are dotted with high-rises and shopping centres that stand out in sharp contrast with a slum situated nearby. We also find that rejuvenation of common property resources such as Madivala lake has changed its access and use, raising questions around who can lay claim to public commons and their ecosystem services.

This first set of photos is a commentary on how urbanisation creates conditions that exclude some sections of the population while privileging others. Using photographs from a scoping field visit within the city of Bangalore in South India, we first contrast two settlements in southern Bangalore – one a highly planned electronic hub with modern amenities and system of independent governance, and the second a peri-urban landscape across the electronic hub that continues to negotiate its rural identity in a fast urbanising context.

In the second set of photographs, we juxtapose slum dwellings and high rise buildings to display inequities in urban living. We also use the example of lake restoration within the city to show how some forms of development may exclude citizens from certain services.

Bangalore city, capital of the state of Karnataka state, is one of the fastest growing cities in India in the past two decades and is an important economic centre in the state. However, similar to other Indian cities, its growth is marred by spatial and income inequalities. According to official estimates, 16.45 per cent of Bangalore’s 8.4 million population live in 597 slums. The urban poor often live in government land though private and railway lands are occupied in some cases. Deprived of basic amenities such as health services, proper sanitation and water access, living in these areas makes people vulnerable to diseases and extreme events and other hazards. The rise of these informal settlements is curtailed through slum clearance (which often denotes slum demolition) with reports of thousands of families being evacuated from their homes in a single night! At the same time, the city has seen an unprecedented rise in construction of private residential enclaves and ‘gated-communities’, often advertised as secure and self-sufficient communities that cater to high-income groups.

This urban dichotomy presents a pressing challenge for city planners. The City Development Plan for Bangalore under the Jawahar Lal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM, GoI 2006) took special notice of these inequities and laid down guidelines for providing basic services to urban poor. However, benefits from JnNURM schemes did not benefit slum dwellers because of inadequate fund allocation and development of plans without consulting stakeholders. Additionally, most schemes are critiqued for worsening existing conditions because they promote resettlement of slum inhabitants to Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) quarters which are often far from livelihood opportunities and lack basic amenities such as access to water and sanitation facilities.

So far, the primary focus of city and state governments has been economic growth and employment creation through large-scale infrastructure development projects. Public policy is skewed in favour of the globalised hi-tech growth sector and does not recognise slums and informal settlements as legitimate parts of the city. Such a model of urban development, characterised by zone-based infrastructural development, intensifies inequity among the rich and the poor in terms of access to services, employment opportunities and development benefits. Existing governance issues such as lack of adequate funds, an understaffed municipal government, overlapping and unclear jurisdictions and lack capacity to tackle existing and emerging urban problems exacerbate Bangalore’s unequal growth trajectory.

Photo credits: Manish Gautam, Chandni Singh, Massimo Ingegno, Shashikala

This scoping visit was part of ongoing research under the Adaptation at Scale in Semi-arid Regions (ASSAR) project. ASSAR is funded by IDRC and DFID under the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA).