China is muscling in on some of Russia’s share in the global market for civil nuclear reactor construction, creating competition for market share and political influence in the Middle East.

While the world’s attention was focused in Spring 2015 on the negotiations between Iran and the P5+1 nations, one of those P5 nations – Russia – was hurriedly racing across the Middle East to sign nuclear plant construction contracts with Iran’s Sunni rivals. In addition to seizing upon a good business opportunity among Iran’s regional rivals, Russia was also attempting to outflank another P5 nation, China, which is emerging as Moscow’s rival in the Middle East market for civil nuclear technology.

Expanding Russia’s global market share in nuclear reactor construction is a policy priority for Moscow. During his first tenure as president of Russia, Vladimir Putin set a national goal of generating 25 per cent of Russia’s electricity from nuclear energy by 2030. Russia has the second largest number of reactors under construction in the world. Preserving its premiere position in the global market for civil nuclear technology is also essential for Moscow’s maintenance of its own nuclear industry. However that position is now threatened by Beijing’s entrance into the global market with a Chinese-designed reactor. To build its brand, China is muscling Russia out of the market in a post-sanctions Iran. China’s emergence as a competing supplier of civil nuclear technology in Iran is one of the principal reasons Russia is scrambling across to secure new markets across the Middle East.

Russia’s first and only project in the Middle Eastern market outside of Iran is Turkey’s Akkuyu nuclear power plant that will feature four Russian-designed VVER reactors. Turkey and Russia held the groundbreaking ceremonies for the project less than two weeks after Iran and the P5+1 nations announced the April 2, 2015 Framework Agreement. The plant is being financed by Russia under a Build-Own-Operate model.

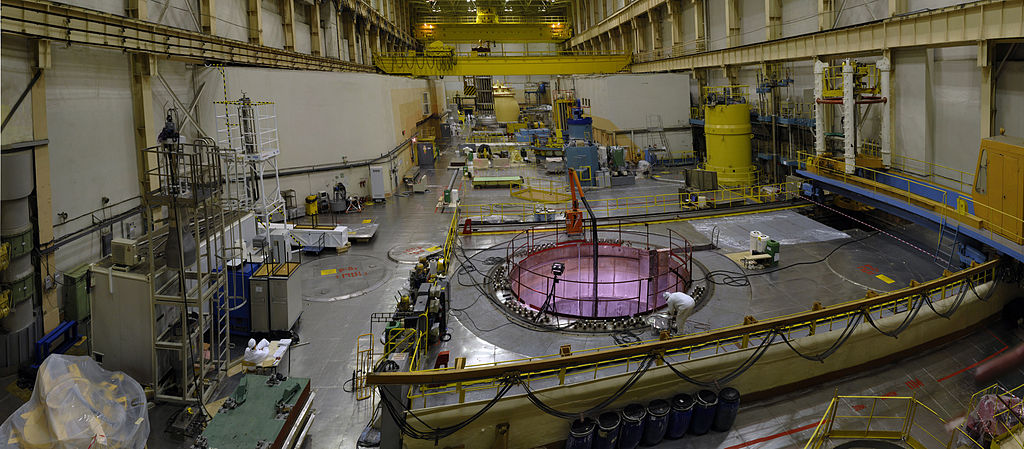

Image by КольскаяАЭС via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russia.Rosatom.KolaNPP.AO.1_Blok-2.jpg

Two months earlier Putin and Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy company ROSATOM to build Egypt’s first commercial nuclear power plant. A month after the Russian-Egyptian MOU, Russia signed a US$10 billion agreement with Jordan to construct the country’s first nuclear power plant, with ROSATOM as 49 per cent stakeholder. In June, a few weeks before Iran and the P5+1 the conclusion of a deal over Iran’s nuclear program, Russia signed an agreement with Iran’s Sunni arch-rival Saudi Arabia that creates the legal framework for bilateral cooperation in civil nuclear development. The agreement was followed by a Saudi commitment to invest $10 billion in Russia.

During the sanctions regime, Russia had a near monopoly as a supplier of materials to Iran’s nuclear program, most notably ROSATOM supplies fuel for Iran’s nuclear facility in Bushehr. To prevent Russia from losing its dominant position in Iran’s nuclear energy sector, ROSATOM signed an agreement with Tehran to construct two new VVER reactors at Bushehr in the short term as well as two more reactors in the medium term. Additionally, the agreement provides for the Russian construction of an entirely new nuclear power plant in Iran with another four of the same Russian-designed, pressurized water reactors.

However, a few weeks after the April 2015 Framework Agreement, Iranian officials met with their Chinese counterparts in Beijing to discuss China’s construction of a near equivalent number of reactors in Iran after sanctions have been lifted. On April 25, 2015, the deputy head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) Behrouz Kamalvandi met with his Chinese counterparts in Tehran to advance the negotiations over China’s construction of a number of nuclear plants in Iran. Earlier in the month, Kamalvandi had announced that China would construct an unspecified number of nuclear power reactors, intimating that Russia’s ROSATOM would be limited in the future to the six reactors it had already be contracted to build .

In 2014, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) approved China’s Hualong One reactor. It was the first time the IAEA approved a Chinese-designed reactor. Beijing hopes its big splash into the Iranian market will build up the brand for the Hualong One, a third generation reactor. Iran’s cooperation seems likely to help China muscle in on some of Russia’s share in the global market for civil nuclear reactor construction. Given Beijing’s success in the Iranian market, China can be expected to follow close behind Russia as a major nuclear exporter to other Middle Eastern markets. Sino-Russian competition for market share as well as for political influence in the Middle East will facilitate the further nuclearization of the region.